This section explores course-specific elements of the language and literature course including the seven concepts, areas of exploration, and global issues. Developing a strong understanding of these elements, and how they drive student inquiry, will help you in your course design journey.

Let’s dive in!

Balance in course design

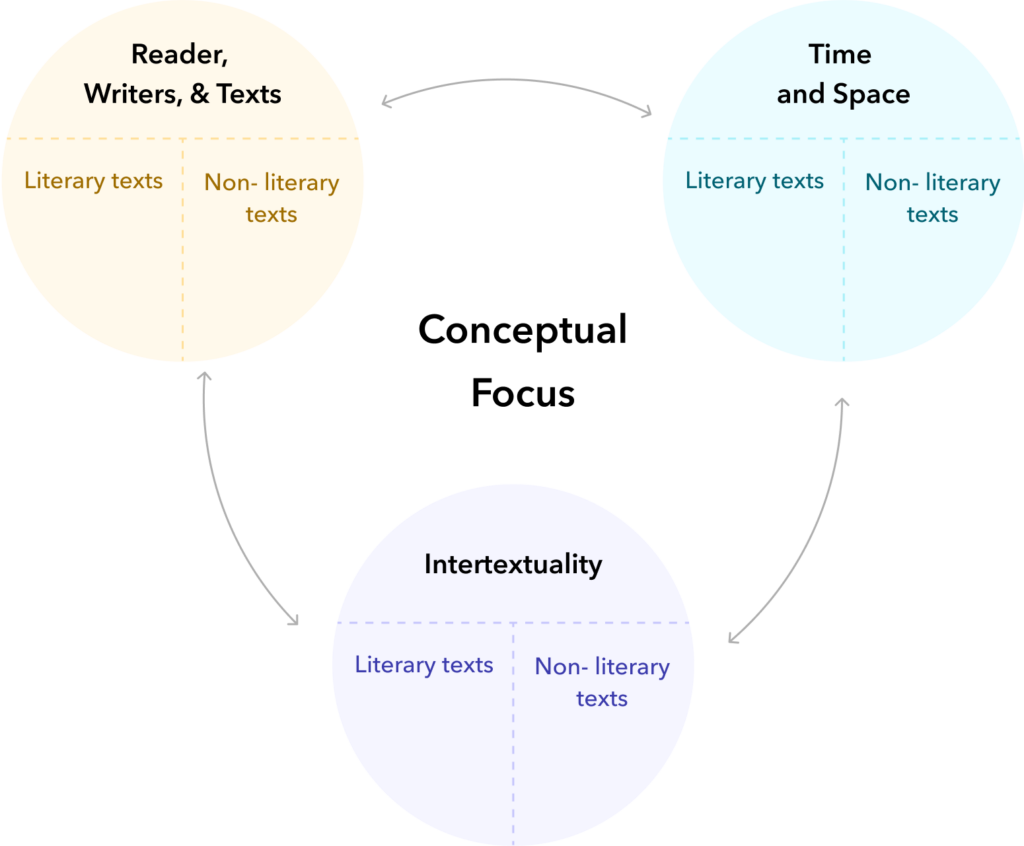

The diagram below is the simplest way to communicate a bedrock principle of course design: balance. In selecting works for study, and in designing classroom learning, there should be a sense of balance between the three areas of exploration, as well as between literary and non-literary works selected for study.

In this course, we study how meaning is constructed and interpreted. You can kickstart the course by introducing your students to the fundamental principle of textual analysis: constructing meaning from literary and non-literary texts requires interpretation. After establishing this baseline understanding, progress to the three areas of exploration, highlighting key definitions and concepts. Unpack all of this and more for your students with this slide deck.

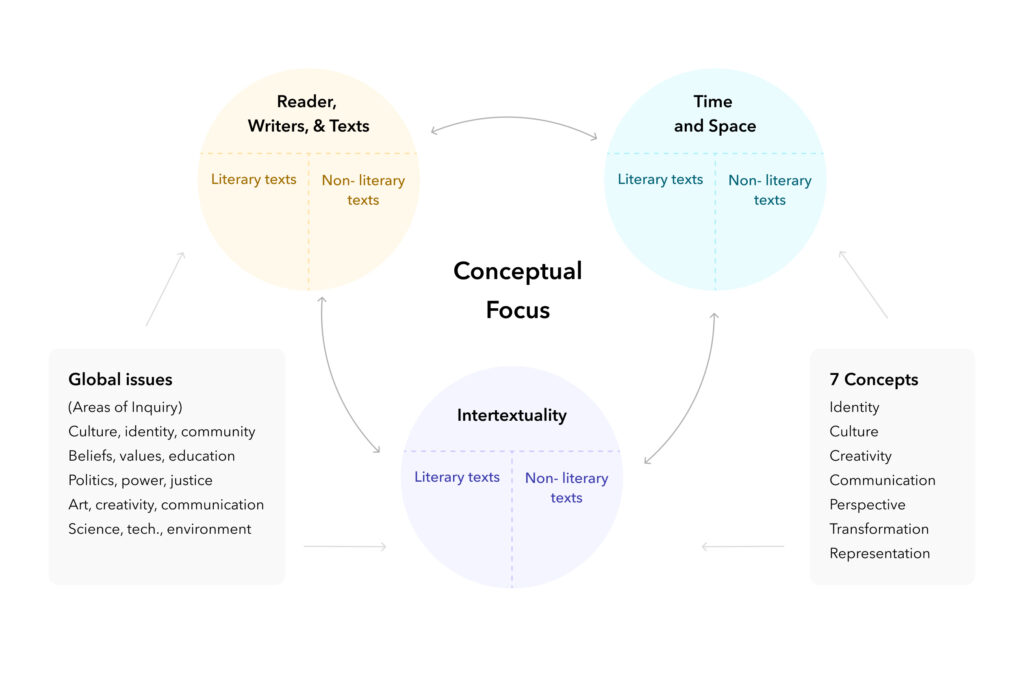

The next image incorporates another layer of complexity you need to consider while constructing the syllabus: global issues and the seven concepts. Approaches to addressing the seven concepts and global issues are more variable, more dependent on which texts are selected for study, and the direction of student curiosity and engagement with specific texts. Global Issues and the Seven Concepts could be introduced to students by using this student-facing Slide Deck: Global Issue Bookmarks.

The following sections focus on the three foundational concepts found in the terrifying diagram above: areas of exploration, the seven concepts, and global issues. Each represents an important aspect of course design, but it is useful here to remember, once again, our primary purpose. We need our students to grow:

- as skilled readers of literary and non-literary texts;

- as critical thinkers capable of examining how meaning is constructed;

- and as skilled communicators, capable of explaining complex ideas with clarity and precision.

The parameters and requirements established by IB provide language and literature educators with an incredibly rich and complex opportunity to think about how a course could and should be constructed. It’s easy to overthink, over-conceptualize, and over-plan. Don’t get lost in the weeds! Don’t count teaching minutes allocated to “Time & Space” versus “Intertextuality” to the detriment of learning in your classroom. Think about what students will need to demonstrate by the end of the course (see Assessments) and chart a path that works for you and your students. Focus on the texts, focus on the experiences your students are having with the texts, and teach them how to write.

Areas of exploration

Areas of Exploration represent different approaches to teaching and learning for the course. They are different conceptual lenses. Each invites students and teachers to investigate literary and non-literary works, textual interpretation, and the construction of meaning from a slightly different perspective. This course syllabus recommends a balance in teaching time between the three approaches.

As units are built, it’s useful to cycle through the areas of exploration. A unit of study will generally consist of an area of exploration, a focus on one or several of the seven concepts, an essential question, and either a literary work / non-literary body of work or a set of related works. It is also possible to construct units that incorporate multiple areas of exploration.

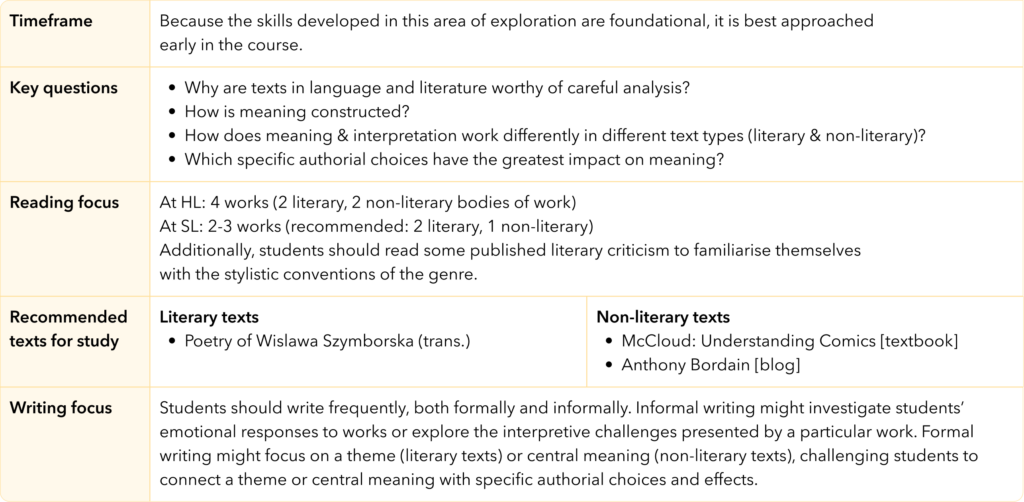

Readers, writers and texts

Students learn to identify and interpret key authorial choices: rhetorical strategies, literary devices, and stylistic choices. They learn how these choices impact the reader emotionally and conceptually. They learn how meaning is communicated and constructed differently in literary and non-literary texts.

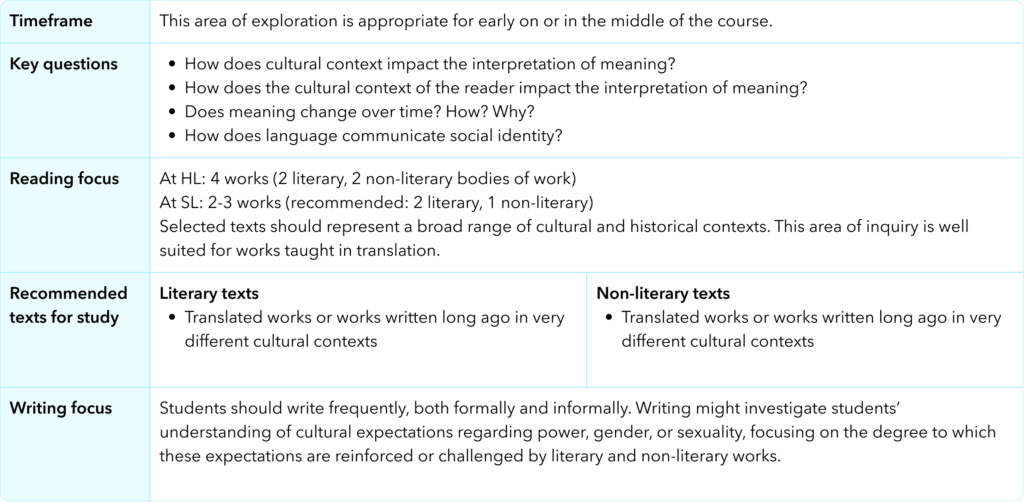

Time and space

Students investigate the impact of cultural context and expectation on the construction of meaning. They view text through the lens of author and audience and consider the ways in which texts represent, reflect, or challenge cultural or historical beliefs about identity and value.

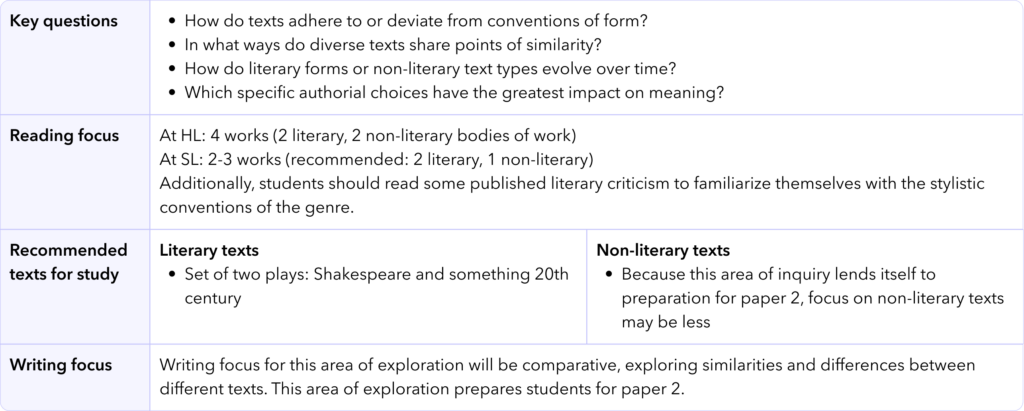

Intertextuality: Connecting texts

This area of exploration is comparative in nature, designed to give students an understanding of the ways in which texts exist in a system of relationships. Texts are studied in groups, linked by genre, form or in some other way. Perhaps the group of texts represents a particular mode: satire or action-adventure. Focus will be on similarities and differences in how texts construct meaning.

The seven concepts

The 7 concepts are a set of useful approaches to textual interpretation. They provide students with a sense of continuity as you move between units of study. Think of each concept as a pair of glasses that can be put on or taken off at any time. During any unit of study, and with any text, for example, it is appropriate and useful to consider identity within the context of the work. How is identity portrayed, as static or changeable? How about the identity of the author? To what extent should this shape our understanding of the work? Ideally, each of the seven concepts is a jumping off point for engaging discussion, an effective tool to support student inquiry.

The following questions are suitable for any literary or non-literary work. Any of these questions would be appropriate for informal “writing-to-think” exercises carried out in the learner portfolio. A printable version of this graphic can be found here. Students can paste it into their portfolios and to access it while writing to think.

Global issues

Global Issues within the context of IB language and literature are not very different from what one would consider global issues outside the context of this course. Hunger, mass incarceration, unjust limitations of individual liberty, climate change, all of these are starting points for the development of what would be considered a Global Issue in this course. Simply put, Global Issues are issues that:

- have significance on a wide/large scale

- are transnational

- have impacts that can be felt in everyday local contexts

We are always looking for meaningful Global Issues in the works we study.

Global Issues are always important. Like the seven concepts, they provide an excellent springboard for engaging thought and discussion. The key questions with respect to global issues are the following: How does the work we are studying present a particular global issue through its content and form? What author or creator choices in style and technique have the greatest impact on how the global issue is represented and explored in the work? Where in the work is the global issue represented most clearly? These questions are formalized in the Individual Oral, which is examined in much greater detail here. For now, those interested in more information can examine this student-facing slide deck: Global Issue Bookmarks.

The learner portfolio

You have tremendous flexibility in how to approach the learner portfolio with your students. Simply put, the learner portfolio is where student work lives. As you progress through the course with your students, you will cover a lot of ground: new vocabulary, new ways of understanding literary and non-literary texts, preparations for course assessments. The learner portfolio exists as both a tool to support this learning and a storehouse for evidence that this learning has occurred. Schools may be required to submit individual learner portfolios to I.B. in cases where academic dishonesty is suspected or to evaluate the implementation of the syllabus in a school.

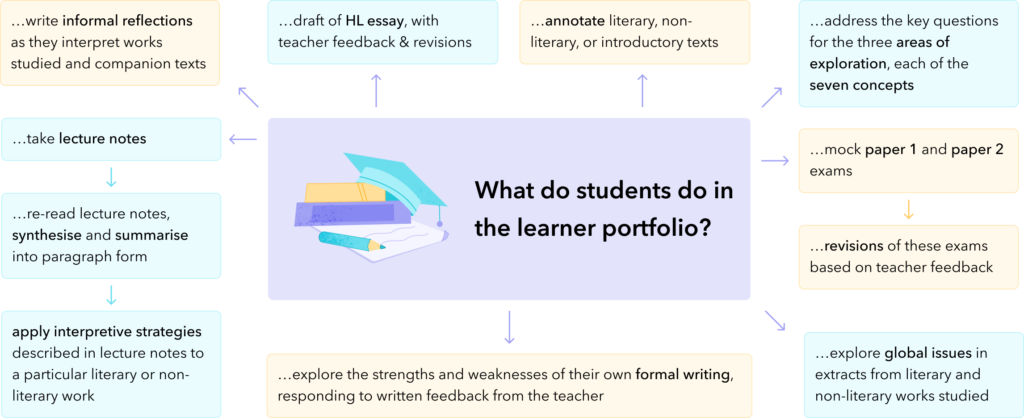

The graphic below represents the range of activities that can take place in the learner portfolio. Learner portfolios can be 100% pen and paper. They can be 100% digital. Or, and this is recommended, they could be some combination of the two.

Recommended approach: physical three-ring binder (2-inch min.) with a composition notebook for pen and paperwork. Dedicated Google Drive folder for Language & Literature course with all files accessible by student and teacher. Which activities are better in digital learning spaces and which are better on paper? The tables below offer some guidance on this question.