Table of contents

Who is an academic leader?

Their roles are as unique as the schools they serve.

At their core, academic leaders are the anchors of a school’s success: driving innovation, supporting teachers, and creating an environment where students can truly thrive. They do this by aligning programs and practices with the school’s guiding principles and helping teachers bring those ideas to life.

Of course, no two roles are the same. Every school has its own needs, but one thing academic leaders all have in common is juggling a whole lot of responsibilities across different stakeholders. They’re often in hybrid roles – part teacher, part administrator – all while keeping up with the changing nature of the world of education.

When you boil it down, academic leadership is really about two big things: building strong relationships and driving academic excellence. Or, to simplify it, bringing together two interconnected halves, people and programs, to create something exceptional.

In this article, we’ll explore these two halves that make up academic leadership and share five practical strategies to help leaders feel confident and successful in balancing them.

People

Connecting with and guiding educators is at the very heart of academic leadership. The way they communicate can make all the difference in determining how eager and willing colleagues are to collaborate. While a school’s structures play a role in shaping the work, the beliefs, assumptions, and mindsets they bring to the table are just as important. And, at the center of it all are 3 crucial things: cultivating a growth mindset, championing growth-minded coaching, and leading cultures of change.

Embodying and fostering a growth mindset

A growth mindset is practically a must for academic leaders, especially as their roles increasingly lean into instructional coaching. It starts with asking the essential questions: How are you committing to your own growth as a leader? Are you staying current with emerging practices in education? How do you connect with others in similar roles whether locally, regionally, or nationally?

And it’s not just about the leader’s mindset. What about their school’s mindsets? These might take the form of core values, guiding documents, or even the frameworks shaping your curriculum. How often are these at the center of a leader’s decision-making?

As an academic leader, making sure the school’s big-picture values are part of their everyday work is what keeps everything aligned and moving forward.

Moreover, a growth mindset helps foster a culture of collaboration. Building an effective collaboration culture starts with defining what that collaboration should look like and maintaining positive group dynamics. Here are two strategies to help a leader in cultivating a growth mindset in a collaborative way:

STRATEGY 1: Identify everyone’s collaboration styles

In his book How To Work With (Almost) Anyone, Michael Bungay Stainer discusses the concept of the “keystone conversation,” in which teams discuss and vision how they will work together on a project. Understanding everyone’s collaboration styles upfront can strengthen relationships and help avoid distractions later on.

Some questions a leader could ask their teachers before starting are:What are the work-related tasks at which you excel?What are your preferences on how to communicate with a team?What is an example of a successful or unsuccessful collaboration you’ve experienced in the past?

STRATEGY 2: Use group maintenance activities

Once the leaders have established how the group will work together, the next step is to maintain that dynamic. People’s needs and preferences shift over time, so as an academic leader, it’s crucial to keep a pulse on the team.

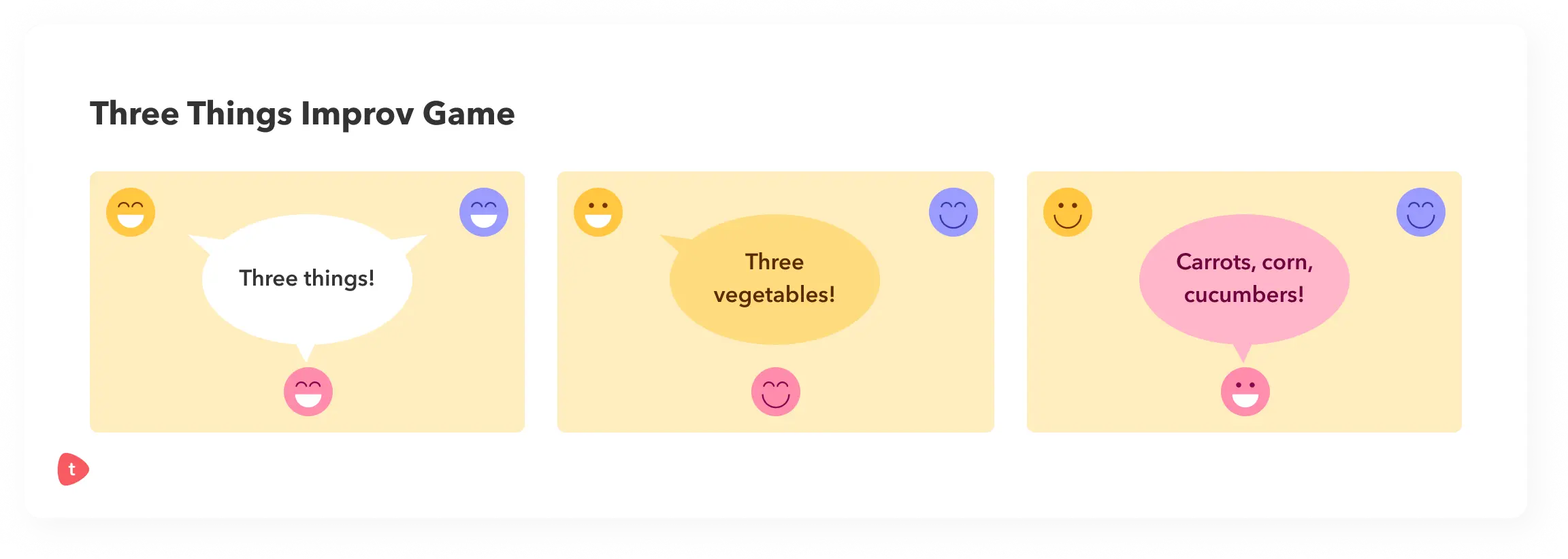

Greg Bamford of Leadership + Design suggests short group maintenance activities at the beginning of collaborative sessions designed to not only take stock in the overall wellness of the group dynamic but also bring group members closer together. These can include playing short improv games such as Three Things, where players take turns naming three things in a specific category, often with spontaneous or funny answers. (e.g., “Three types of hats”), and another quickly responds with three answers before passing to the next player. Or, running a high-energy rock-paper-scissors tournament, where losing players become cheerleaders for the winners until one champion remains.

These activities might only take five minutes, but the payoff is huge. They boost group morale, strengthen relationships, and set the stage for long-term success in all collaborative projects.

Championing growth-minded coaching

As mentioned earlier, bringing a growth mindset to your interactions with colleagues is essential. One way to champion this is through the types of conversations you have about their practice.

STRATEGY 3: Using growth-minded coaching language

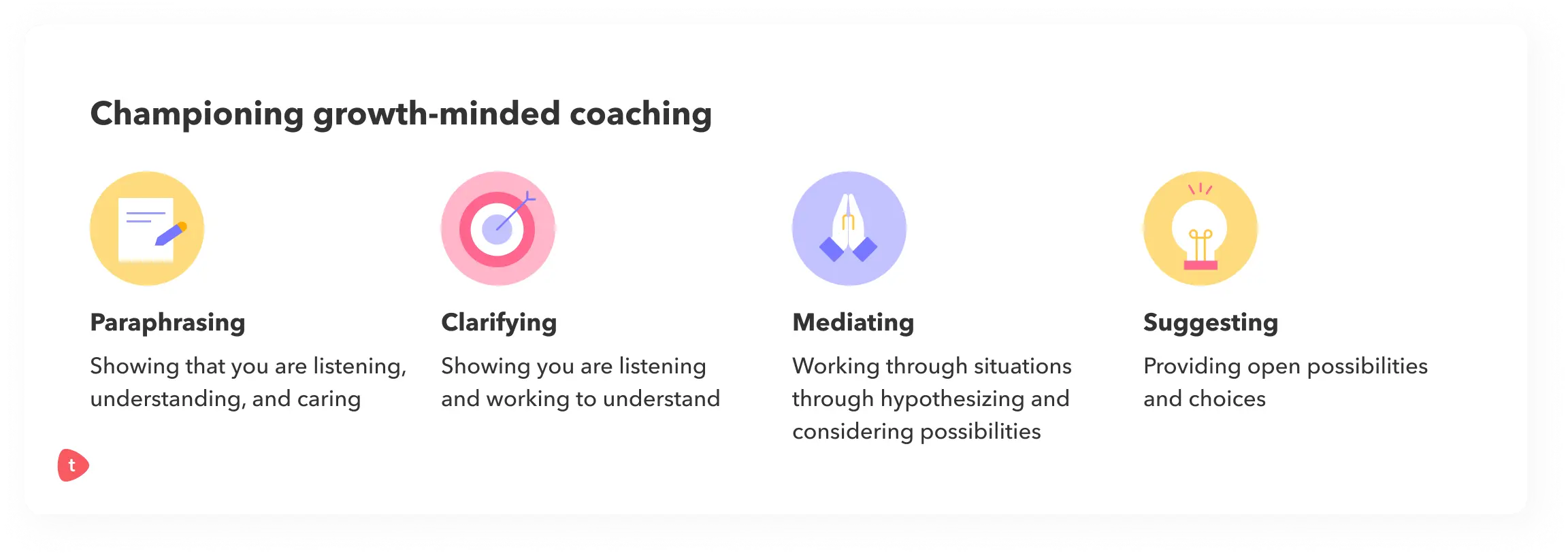

Dr. Emily Davis, founder of the Teacher Development Network, describes four types of language to use in growth-minded coaching:

Paraphrasing: Showing that you are listening, understanding, and caring

“It sounds like you’re concerned about how the students are engaging with the new curriculum.”

“You’re saying you want to try new strategies, but you’re unsure where to start?”

Clarifying: Showing you are listening and working to understand

“Can you tell me more about what you mean by ‘the students aren’t connecting’?”

“When you say the group isn’t collaborating effectively, what specific behaviours are you noticing?”

Mediating: Working through situations through hypothesizing and considering possibilities

“What do you think might happen if you allowed students more time for group discussions?”

“How do you think it would change the dynamic if you adjusted the seating arrangements?”

Suggesting: Providing open possibilities and choices

“Have you considered breaking the task into smaller chunks to make it feel more manageable?”

“One option might be incorporating movement activities to re-engage the class. How does that sound?”

At the core of all these methods is language that centers on the educator: acknowledging their feelings and perspectives while gently guiding them toward practices aligned with the school’s principles.

It’s about presenting options, not directives, and empowering them to choose their next steps.

None of this can happen unless you carve out time to support your teachers. Independent School Management suggests that 25–50% of your weekly schedule should be focused on supporting educators in aligning their practices with your school’s guiding principles. If that feels like a tall order, you can start by blocking time on your calendar for classroom visits or 1:2 teacher meetings and protecting that time by saying no to meetings that don’t directly support teacher growth.

You can also take small steps such as spending 15 minutes from your prep period observing a class and offering timely feedback or just initiating a conversation.

Leading Cultures of Change

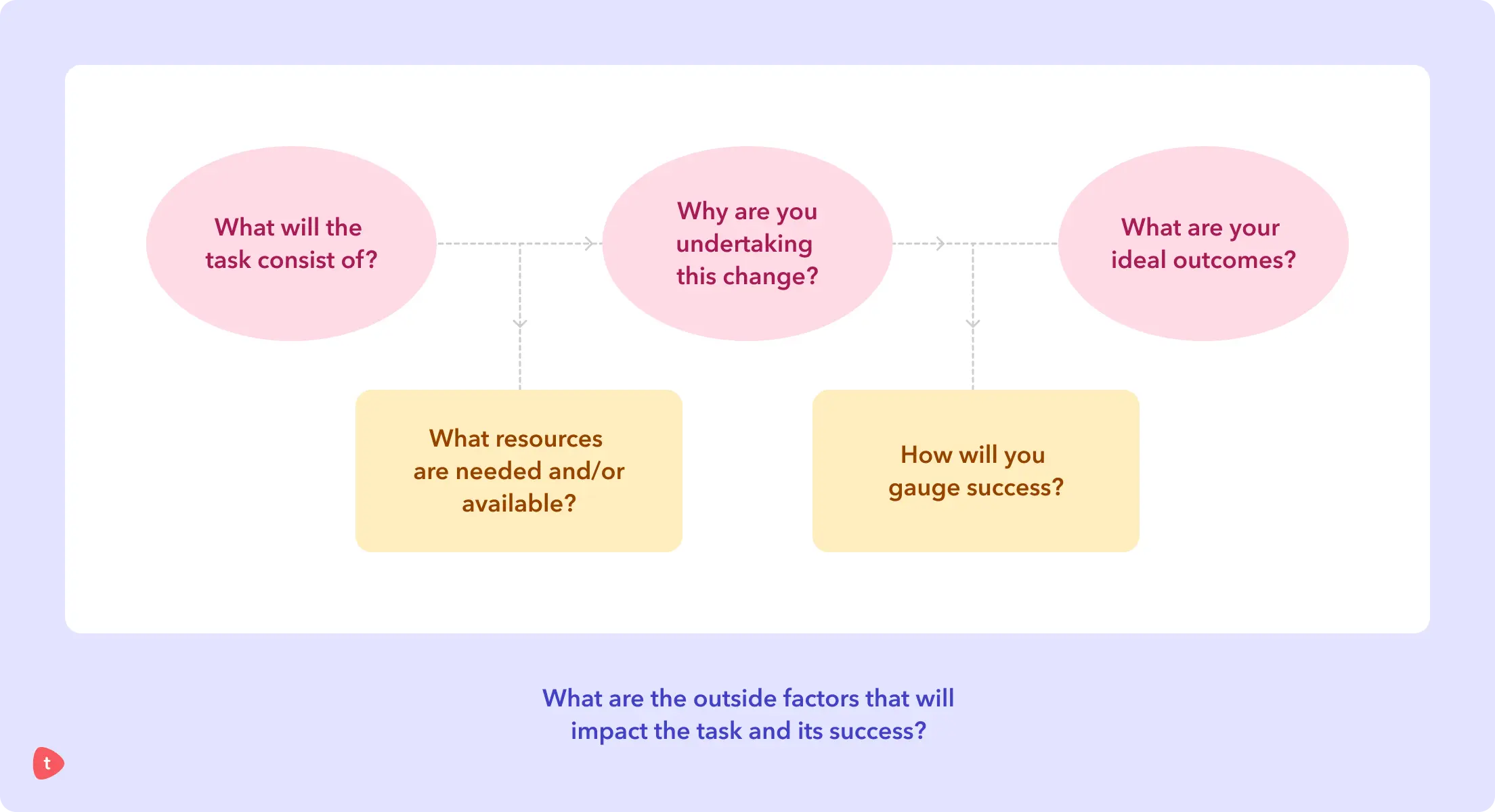

Academic leaders must cultivate and lead cultures of change within their schools. In order to do that most effectively, they must determine the flow of change within their school: how does change happen? Who needs to be involved? What resources are available and needed? What are the outside pressures on the work?

STRATEGY 4: Use systems map

Tim Fish, founder and president at Two Chairs Studio and formerly Chief Innovation Officer at NAIS, suggests using a systems map to plot out the course of change in advance.

A system map is a visual tool that helps leaders plot out the different elements, processes, and relationships that affect change within a school. It encourages leaders to consider the broader picture, including the various stakeholders, resources, goals, and potential barriers to success.

Systems maps should ask:

Why are you undertaking this change?

What are your ideal outcomes?

How will you gauge success?

What will the task consist of?

What resources are needed and/or available?

What are the outside factors that will impact the task and its success?

Small, intentional steps toward supporting educators can have a ripple effect: building trust, strengthening practices, and reinforcing your role as a growth-minded leader.

Program

The educational landscape in 2025 poses unique challenges for academic leaders. Schools are not immune to the erosion of trust in institutions that has occurred since the 1970s and the COVID-19 pandemic has widened achievement gaps. In addition, the meteoric rise of generative artificial intelligence (AI) has put it on a collision course with academic programs. For leaders, it’s essential to navigate these shifts while continuing to drive academic excellence for their schools.

At the center of it all is curriculum.

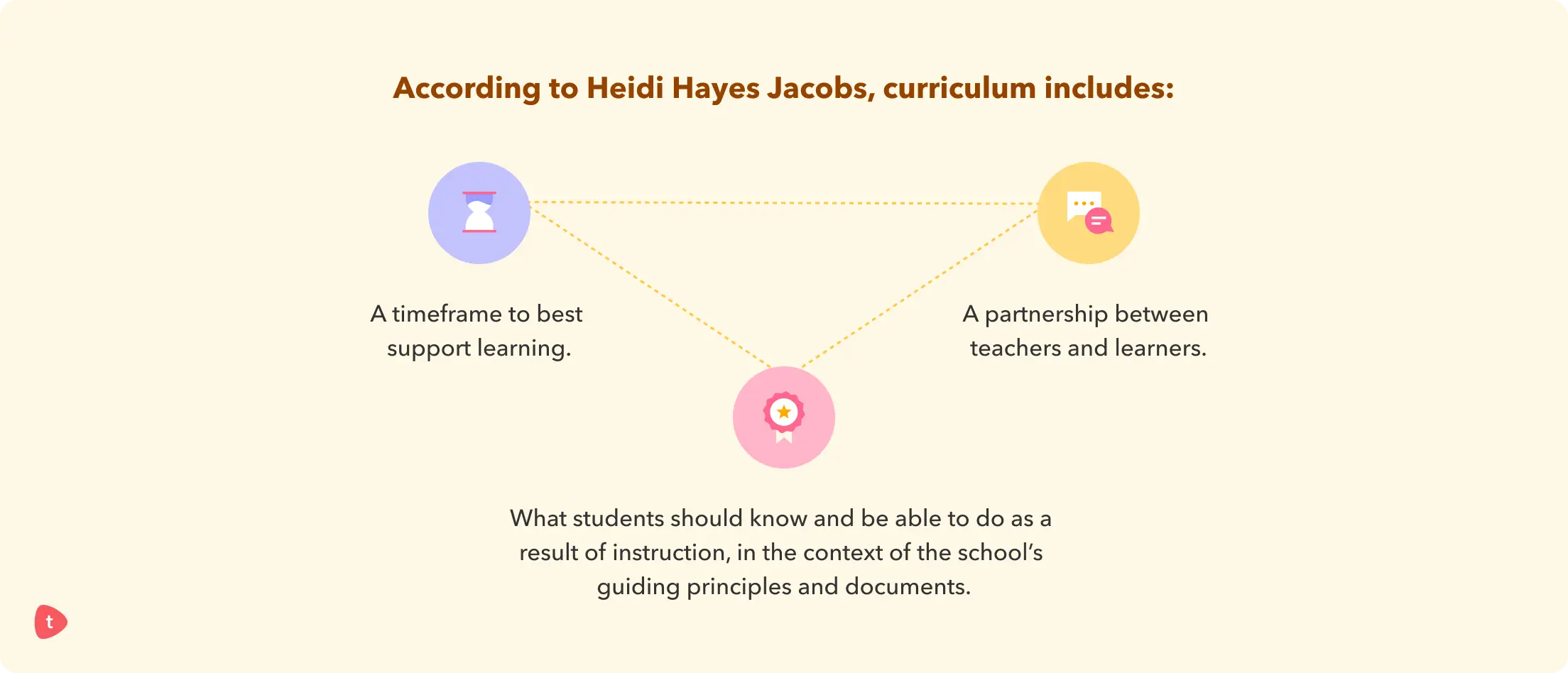

The Academic Leader Forum’s session with Heidi Hayes Jacobs was a goldmine in exploring the fundamental questions about what curriculum is and is not.

From Latin, “curriculum” means “a path to run in small steps” or “a course to run.” This aligns with the understanding of curriculum as the means and timeline by which we achieve the goals for our students as outlined in our schools’ guiding principles and documents. While we often discuss curriculum in the broad sense, we may not always think about its constituent parts. According to Heidi Hayes Jacobs, curriculum includes:

- What students should know and be able to do as a result of instruction, in the context of the school’s guiding principles and documents.

- A timeframe to best support learning.

- A partnership between teachers and learners.

Curriculum includes:

- What students should know and be able to do as a result of instruction, in the context of the school’s guiding principles and documents.

- A timeframe to best support learning.

- A partnership between teachers and learners.

It is also important to note what the curriculum is not. Curriculum is not a purchased program or textbook or standards. While standards are spinal to curriculum, meaning that they can help provide guideposts to help provide organization, they are in service to that curriculum and not the curriculum itself.

So how can leaders ensure that their school’s curriculum reflects the school’s aspirations directly? Lauren M. Kaufman identifies four key principles necessary for academic leaders to follow as they approach curriculum: effective communication, consistent collaboration, focused implementation, and adaptive flexibility. While we discussed communication, collaboration, and implementation in detail in the article above, it’s crucial to pay attention to the aspect of adaptive flexibility.

Flexibility is essential in a curriculum that values both teachers and learners, as educators can adapt and respond nimbly to students’ needs. When the curriculum is focused upon helping students aspire to the school’s guiding principles, teachers can be encouraged to adapt in ways that are most beneficial to their learners. By adapting in these ways, leaders build a partnership between teachers and learners. Jacobs says it is essential to a healthy and attainable curriculum and encourages academic leaders to streamline their curriculum to get there.

Jacobs uses the word streamlining intentionally: streamlining is to simplify to make something more desirable, or more elegant, or smoother. Streamlining, in a curricular sense, helps teachers and learners focus on what matters most. In order to streamline your curriculum, you need to ask three basic questions, that often have complex responses:

- What do you need to cut?

- What do you need to consolidate?

- What do you need to create?

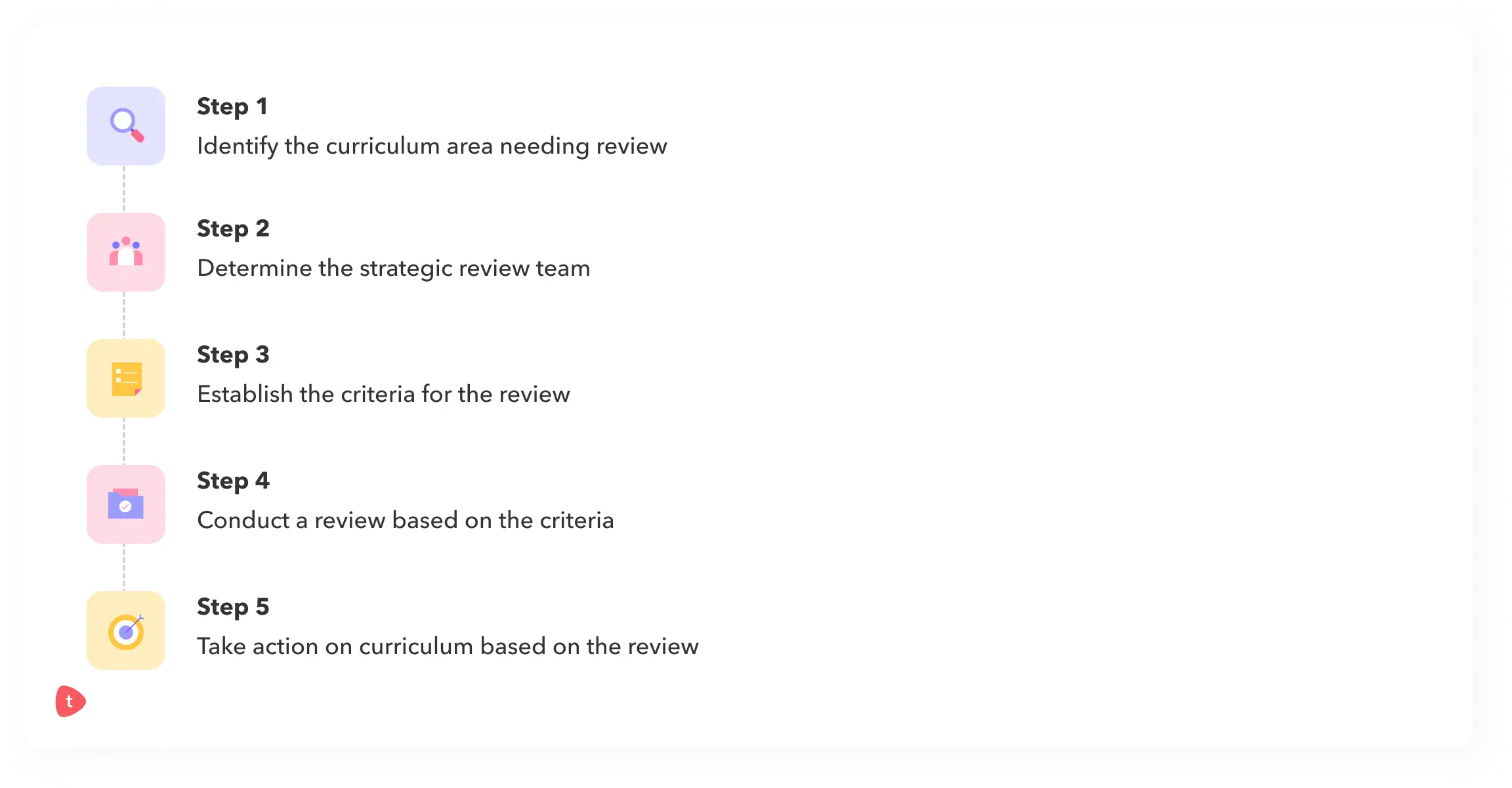

STRATEGY 5: Apply the curriculum review process

In order to best respond to these questions, Heidi Hayes Jacobs and Allison Zmuda have developed a five step curriculum review process for academic leaders to use:

Identify the curriculum area needing review: What is the specific aspect of the curriculum you believe needs work? Are you looking at courses from a vertical alignment perspective? Are you looking at specific units of study, either in a single course or program or across multiple courses or programs?

Determine the strategic review team: What are the possible groups or teams that can come together to work through these choices? Would an established group, such as a curriculum committee or department, or an ad hoc task force be most effective? Consider your keystone conversations when forming the group.

Establish the criteria for the review: With your team in place, determine what needs to be cut out, cut down, consolidated, and created to streamline your curriculum.

Conduct a review based on the criteria: Using the established criteria, investigate, discuss, and document potential changes to the curriculum. Be sure to utilize group maintenance throughout the process to ensure your group is working to its full potential.

Take action on curriculum based on the review: With the team and beyond, begin to implement those actions that will help you streamline your curriculum according to the criteria you set.

If you are a leader looking into ways to enhance the partnership between teachers and learners through your curriculum, as well as encourage your colleagues to become creators and composers of curriculum, instead of just coverers, consider exploring curriculum storyboarding, which helps transform curriculum from a documentation of coverage to a narrative that is built upon connections, engagement, investment, and cohesion.

Closing remarks

Academic leadership is such an exciting and important role, one that’s shaped by the unique perspectives and experiences each leader brings to the table. Recognizing how their background influences their approach can be a real strength. For instance, a leader with a social studies background stepping into an all-school academic role might naturally view challenges through a humanities lens, which can bring fresh insights. By embracing this perspective and collaborating across disciplines, they can create a more balanced and connected approach to leadership.

With clear frameworks to guide them, like understanding their leadership lens, fostering strong connections across departments, and aligning practices with their school’s vision, leaders can take on their responsibilities with optimism and confidence. This thoughtful and proactive approach not only helps them support their colleagues but also inspires meaningful progress, ensuring their school continues to thrive.

Table of contents